Bayern Munich fans hoping for a few transfer bombs next summer may need to lower their expectations. Uli Hoeness, a member of Bayern’s supervisory board, has ruled out the idea that the top club will make major moves in the transfer market.

Bayern Munich supporters hoping for a summer full of blockbuster signings may have to reset their expectations.

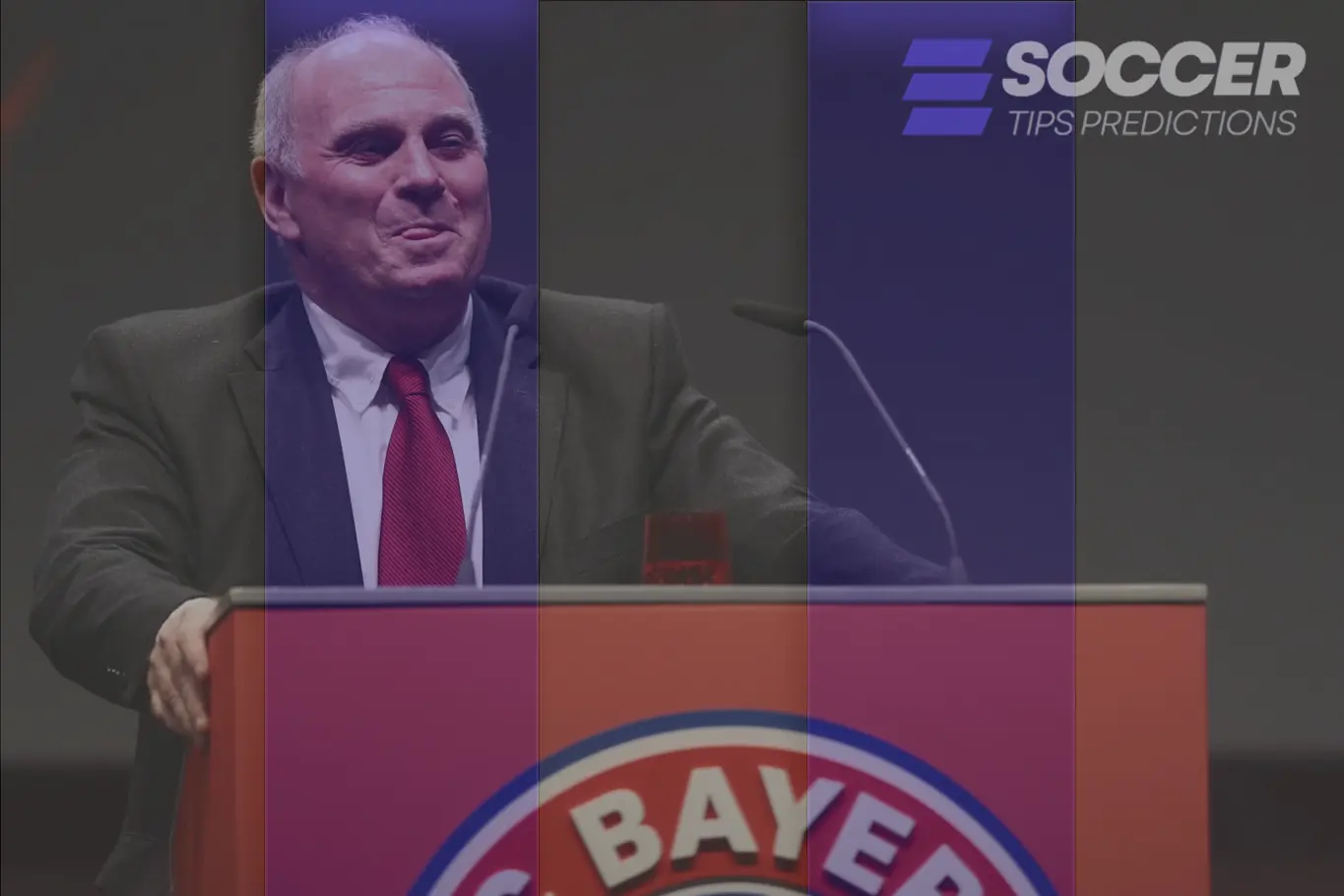

Uli Hoeness, the 74-year-old supervisory board member and one of the most influential figures at the club, has made it clear that Bayern do not intend to “make any big moves” in the upcoming transfer window. Speaking to Bild, Hoeness stressed that Bayern’s identity in the market is rooted in financial discipline, not reckless spending, even when the club’s name is constantly linked to high-profile targets.

“We won’t make any big moves in the transfer market this summer,” Hoeness said. “Transfers must never put us into debt, that is the credo at Bayern. Otherwise there is no room left to compensate. When we noticed that our savings account was getting smaller and smaller, we immediately hit the brakes.”

His comments reveal a club that is taking a more cautious approach after a period in which Bayern, while still considered relatively controlled compared to some European rivals, did pay major fees to reinforce the squad. Hoeness’ central argument is that Bayern will not allow transfer ambitions to erode the club’s financial security. In other words, Bayern may still act, but they want to do it from a position of strength, with cash available, not by borrowing or relying on future revenue to cover today’s spending.

Hoeness also pushed back on the idea that Bayern are in any kind of danger. He insisted there is no need to fear that Bayern’s savings will run out in the near future. The warning, in his view, is not that the club is poor, but that even Bayern have limits if they try to chase every rumour and every expensive name that appears in the media.

“But if we had bought all the players we have been linked with, we would have nothing left now,” Hoeness explained. “Then we would have had to take out loans to finance transfers. At that point we said no.”

That line is telling because it hints at a broader frustration Bayern have had for years: the club gets associated with dozens of players every window, and the public sometimes assumes Bayern can or will sign several of them. Hoeness is effectively saying that the volume of rumours has become detached from financial reality, and that Bayern are drawing a hard line under a principle they do not want to compromise: no debt-driven recruitment.

According to Bild, Bayern’s financial cushion is not as “overflowing” as it was for many years, and there is even talk that the club could face its first loss in a financial year in a long time. Hoeness was quick to calm any alarm, emphasizing that Bayern still have reserves, and that sporting success this season is also creating unexpected revenue.

“We still always have reserves,” he said. “And sportingly it is going very well this season. We have won seven times in the Champions League, that brings in fourteen million euros. We had not even budgeted for that.”

That Champions League reference is important because it shows how Bayern are thinking about the relationship between performance and financial flexibility. Winning brings prize money and matchday value, but Bayern do not want to build a spending plan that assumes a perfect sporting scenario. Hoeness suggests that some of the Champions League income was effectively a bonus rather than a guaranteed line in the budget, and Bayern prefer to keep it that way: treat additional revenue as upside, not as money that must immediately be reinvested into transfers.

So what does a “quiet” Bayern summer actually look like? It does not necessarily mean no signings. It likely means a more selective strategy: fewer arrivals, more targeted profiles, and potentially more emphasis on internal solutions, youth development, and smart market opportunities rather than headline purchases. Bayern have traditionally liked to operate this way, especially when they believe the core of the squad is strong enough and helps reduce the need for constant expensive rebuilding.

At the same time, Hoeness’ remarks are striking because they come after a period in which Bayern have, in fact, spent heavily by their own historical standards. Recent years have included major fees for marquee names: Harry Kane cost close to one hundred million euros, Luis Díaz arrived for 70 million euros, and players such as Michael Olise, João Palhinha, and Min-Jae Kim were all signed for more than fifty million euros each. Bayern may be “frugal” compared to state-backed clubs, but they have not been shy about paying premium prices when they believe a player is a decisive upgrade.

This is precisely why Hoeness’ message carries weight. It signals a shift from the idea of continuous big-ticket spending toward a model where Bayern want to consolidate, protect liquidity, and avoid inflationary bidding wars. It is also a reminder that even the biggest clubs in Germany cannot ignore the broader financial environment of modern football, where wages are rising fast and transfer fees for top-level talent often become detached from traditional valuation logic.

One subplot that could be felt outside Munich is the situation around Paul Wanner. For PSV Eindhoven, the fear is not necessarily that Bayern will go on a spending spree, but that Bayern could still act opportunistically where it suits them. Wanner’s case is presented as exactly that: Bayern can reportedly buy back the playmaker for a relatively modest fee. From Bayern’s perspective, that would not count as a “big move” at all, even if it has significant consequences for PSV’s planning. It is the kind of transaction that fits Hoeness’ model perfectly: controlled cost, limited risk, and a clear sporting logic.

Hoeness’ comments also hint at what Bayern might prioritize if they do enter the market: value, sustainability, and minimizing long-term commitments that could become difficult to unwind. That can translate into more loan deals, more performance-based structures, or more players who fit a specific tactical need rather than a marketing headline. It can also mean Bayern will be more active on the sales side, looking to balance the squad and reduce wage load before bringing anyone in.

Ultimately, the tone from Hoeness is clear. Bayern do not want a summer defined by “transfer fireworks.” They want to remain Bayern: powerful, competitive, but controlled. For fans, it may be less exciting in terms of big names. For the club, it is presented as the responsible choice, aimed at keeping Bayern strong not just for the next window, but for the next decade.